Esther Honens’ spirit continues to support musical excellence

Story by Heather Setka

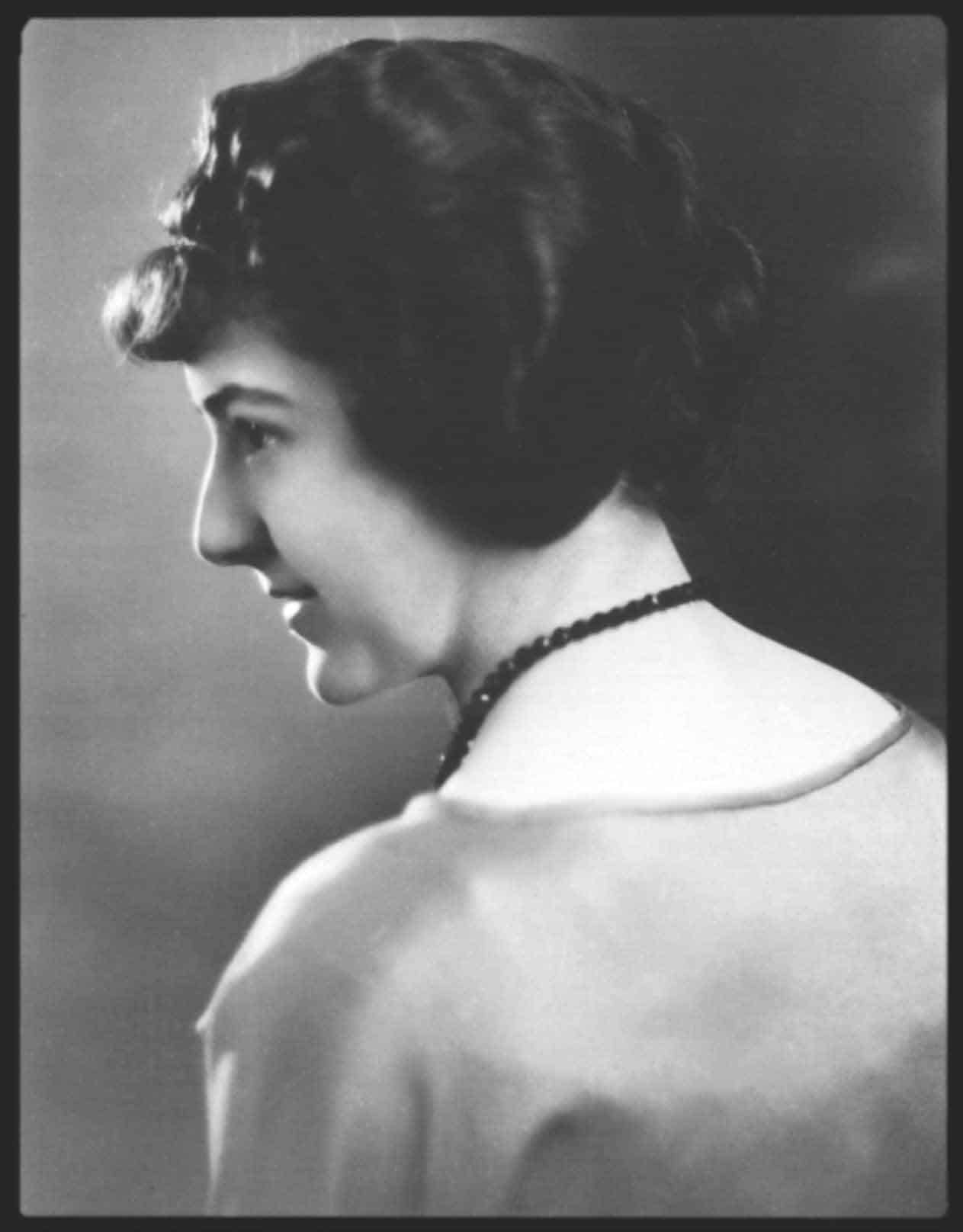

SHE’S WELL KNOWN in the international music community for the festival named in her honour. But many Calgarians have no idea of the impact Esther Honens has had on people’s lives, both locally and globally — even after her death in 1992.

“She loved this city,” says Heather Bourne, interim president for Honens, the non-profit organization named for its benefactor. “And she wanted to give something to this city.”

That gift is the Esther Honens International Piano Competition, which offers rising stars the chance to develop their passion and expertise. Today offering $100,000 in prizes and a world-renowned artist development program, it’s a lasting tribute to a woman who loved music and her community.

Honens’ life reads like a classic novel. Born Esther Smith in Pittsburgh in 1903, she moved to Calgary at age five with her parents and older sister Ruth. The sisters began piano lessons early, and Esther “lived her life in [a] state of musical love,” writes author Iris Nowell in her book, Women Who Give Away Millions.

However, Honens wasn’t a professional musician herself. Rather, she was a successful entrepreneur. She married late, in her early 50s, to real estate investor John Hillier. Through land developments during an early oil boom, Honens became a “wealthy woman,” Nowell writes.

Hillier died in 1971 and Esther married again, at age 71, to rancher Harold Honens.

Her lawyer, Don Hatch, characterizes Esther Honens as a “careful and astute” businessperson as well as a “gracious and wonderful” woman.

“She was really quite remarkable,” Hatch says. He remembers the moment Honens proposed a music competition for Calgary. She’d attended a competition in Texas and she wanted to build something similar here.

A major contributor to the arts throughout her life, Honens began work on her legacy competition in the late 1980s. In 1991, she created the inaugural competition with a $5 million endowment gift from the Calgary Foundation.

Diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, Honens felt her health failing drastically. The competition was moved up a full year so she could see it realized, taking place Nov. 13 to 28, 1992. It brought pianists from all over the globe — Austria, Brazil, Yugoslavia, and Taiwan, to name a few — to compete for a $20,000 grand prize.

It wasn’t just about money. Honens hoped to showcase Calgary’s community spirit, while nurturing international talent. “She seemed to understand the value of technically brilliant pianists and the importance of reaching deeper,” Bourne says.

Hatch says Honens watched the competition from a private booth at the back of the Jack Singer Concert Hall. “She was quite delighted and very grateful,” he says. “It filled her with satisfaction and pride.”

Honens died five days later. The competition’s first laureate, Wi Yu, was flown in from Argentina to play at her funeral.

Her lasting legacy includes grants that support other musical events and organizations, including the Calgary Performing Arts Festival, the National Music Centre, the Calgary Choral Society, the Calgary Philharmonic Orchestra and much more. Honens’ tombstone in Calgary’s historic Union Cemetery reads simply: In Loving Memory.

“There are forces of nature in this world,” Bourne says. “And she was one of them.”

Dated Spring 2015